The Babri Masjid was a mosque located in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, India. Its history is complex and has been a source of religious and political controversy. Here is an overview of the key events in the history of the Babri Masjid:

Babri Masjid India – History and Demolition

- Construction: The Babri Masjid was built in the 16th century during the Mughal rule in India. It is believed to have been constructed in 1528 by order of the first Mughal Emperor, Babur, on the site where Hindus believe Lord Ram’s birthplace is located.

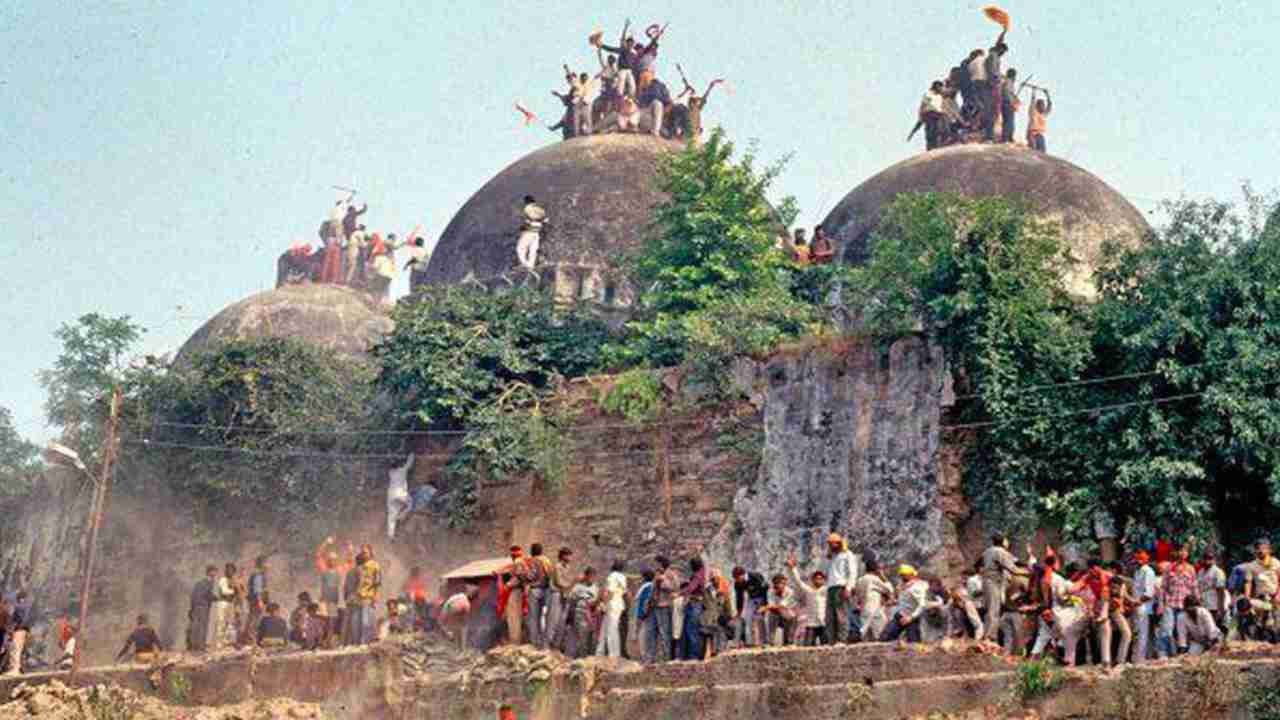

- Dispute and Demolition: The site became a point of contention between Hindus and Muslims over the centuries. In 1992, a large crowd of Hindu nationalists gathered at the site, claiming that the mosque was built on the ruins of a temple dedicated to Lord Ram. On December 6, 1992, the mob, consisting of supporters of the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP), the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and other Hindu nationalist groups, tore down the mosque. This event led to widespread communal violence across India.

- Ayodhya Dispute: The destruction of the Babri Masjid triggered a prolonged legal and political battle over the ownership of the site. Hindus claimed the land as the birthplace of Lord Ram and sought to build a temple (Ram Mandir) in its place. Muslims, on the other hand, demanded the reconstruction of the mosque.

- Legal Proceedings: The Ayodhya dispute went through various legal proceedings in Indian courts. In 2010, the Allahabad High Court ruled that the disputed land should be divided into three parts, with one-third going to the Hindu deity Ram Lalla Virajman, one-third to the Sunni Waqf Board, and one-third to the Nirmohi Akhara. Both Hindu and Muslim groups appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

- Supreme Court Verdict (2019): In November 2019, the Supreme Court of India delivered a historic verdict. The court granted the entire disputed land to the Hindus for the construction of a temple, while directing the government to provide an alternative piece of land to the Muslims for the construction of a mosque. This decision aimed to bring closure to the long-standing dispute and promote communal harmony.

The Babri Masjid demolition and the subsequent legal battles have left a lasting impact on India’s social and political landscape, contributing to heightened religious tensions and shaping the country’s narrative on secularism and religious harmony

The Babri Masjid, located in Ayodhya, India, has been at the center of a dispute between Hindus and Muslims since the 18th century, with Hindus believing it was constructed on the hypothesized birthplace of Lord Rama. Built in 1528–29 by Mir Baqi, a commander of Emperor Babur, the mosque faced destruction in 1992 by a Hindu nationalist mob, leading to widespread communal violence.

Situated on the Ramkot hill, Hindus claim that it replaced a pre-existing Rama temple, a contention contested by some. Archaeological excavations, prompted by the Allahabad High Court, revealed materials suggesting a Hindu structure beneath and contradicted the notion of vacant land. Conflicts and court disputes between Hindus and Muslims emerged in the 19th century, intensifying in 1949 when idols of Rama were placed inside the locked mosque.

The demolition in 1992 by activists triggered riots, resulting in approximately 2,000 deaths. In 2010, the Allahabad High Court awarded the disputed site for the construction of a Rama temple and a portion for a mosque. The Supreme Court, in 2019, quashed the lower court’s judgment, allocating the entire site for the Hindu temple and an alternative 5-acre plot for a mosque, which began construction in January 2021 in the village of Dhannipur, near Ayodhya

Etymology

The etymology of the name “Babri Masjid” is closely tied to the Mughal emperor Babur, under whose rule it is believed to have been built. The mosque derived its name from Babur, signifying its association with the emperor. The historical connection to Babur is emphasized in the nomenclature, reflecting the era of its construction.

Prior to the 1940s, the mosque was known by the name “Masjid-i Janmasthan,” which translates to “mosque of the birthplace.” This name highlights the significance of the mosque’s location, as it is believed by many Hindus to have been constructed on the site considered to be the birthplace of Lord Rama. The term “Janmasthan” underscores the religious and cultural context of the mosque, a fact evident even in official documents of that time. The shift in the name from Masjid-i Janmasthan to Babri Masjid over time is reflective of the evolving historical and cultural narratives surrounding the mosque

Architecture

Background

The background of the Babri Masjid is rooted in the rich tradition of Indo-Islamic architecture, characterized by the patronage of art and construction by rulers of the Delhi Sultanate and their Mughal successors. This period saw the creation of numerous tombs, mosques, and madrasas, each reflecting a distinctive architectural style influenced by the “later Tughlaq” architecture. The rulers were known for their support of the arts, resulting in the construction of structures that showcased a blend of various artistic influences.

Throughout India, mosques were built in diverse styles, with the most refined ones emerging in regions where indigenous art traditions were robust, and local artisans possessed high skills. The architectural styles of these mosques were often influenced by local temple or domestic styles, shaped by factors such as climate, terrain, and available materials. This diversity is evident in the significant differences between mosques in regions like Bengal, Kashmir, and Gujarat.

The Babri Mosque itself followed the architectural school of the Jaunpur Sultanate. When observed from the west side, it bore a resemblance to the Atala Masjid in Jaunpur. This architectural connection highlights the intricate interplay of regional influences and historical legacies that contributed to the unique design and construction of the Babri Masjid within the broader context of Indo-Islamic architecture

Style of Architecture

The architectural style of the Babri Masjid closely resembles the mosques found in the Delhi Sultanate, reflecting the influence of the prevalent architectural trends during that period. As an essential mosque with a distinct architectural style, Babri’s design is a replica of the mosques established in the Delhi Sultanate. This unique style is notably preserved in the architectural features of the mosque, distinguishing it from other structures of its time.

The influence of this architectural style is not limited to the Babri Masjid alone; it can also be observed in other mosques, such as the Babari Mosque in the southern suburb of the walled city of Gaur. Another notable example is the Jamali Kamili Mosque, constructed by Sher Shah Suri. These mosques, including Babri, share common elements that mark a distinct style developed after the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate. The architectural legacy of these structures is considered a precursor to the Mughal architectural style that would later be embraced and further refined during the reign of Akbar

Acoustics

The acoustic features of the Babri Masjid were notable, as mentioned by Graham Pickford, the architect to Lord William Bentinck (1828–33). Pickford reported that a whisper from the mihrab (prayer niche) of the mosque could be distinctly heard at the far end, a distance of 200 feet (60 meters), and across the entire central court. This exceptional acoustic quality was highlighted in Pickford’s book “Historic Structures of Oudhe,” where he commended the mosque’s advanced deployment and projection of voice from the pulpit. Considering that the mosque was built in the 16th century, Pickford found the unique deployment of sound in the structure to be particularly astonishing, emphasizing its architectural and engineering prowess in the context of that era. The acoustics of the Babri Masjid added an intriguing dimension to its architectural significance

Unraveling the Mysteries: The Construction of Babri Masjid

Date and Uncertainty: The exact date of the construction of the Babri Masjid remains shrouded in uncertainty. Inscriptions on the premises claim it was built in 1528–29 by Mir Baqi as per the wishes of Babur, the Mughal emperor. However, doubts arise about the authenticity of these inscriptions, with suggestions that they might be of a more recent origin.

Silent Chronicles: Curiously, historical records from the period of construction do not mention the Babri Masjid. The Baburnama, Chronicles of Babur, and works like the Ramcharitamanas of Tulsidas and Ain-i Akbari by Abu’l-Fazl ibn Mubarak make no reference to either the mosque or the supposed destruction of a temple. Even William Finch, an English traveler in 1611, recorded ruins in Ayodhya but made no mention of a mosque.

Jai Singh II’s Documentation: The earliest recorded mention of a mosque at the disputed site comes from Jai Singh II, a Rajput noble in the Mughal court, in 1717. His documents include a sketch map depicting the Babri Masjid with three temple spires and a courtyard labeled “janmasthan” (birthplace). This intriguing document provides a historical snapshot of the site’s early configuration.

European Perspectives: European Jesuit missionary Joseph Tiefenthaler, residing in India from 1743 to 1785, added another layer to the Babri Masjid’s history. According to his accounts, Aurangzeb demolished the Ramkot fortress, replacing it with a mosque. However, he also noted conflicting beliefs, stating that “others say that it was constructed by ‘Babor’ [Babur].” Tiefenthaler’s observations offer insights into the ongoing disputes and religious practices surrounding the site.

In the next part of this series, we’ll delve further into the complex history of the Babri Masjid, exploring the evolving narratives and controversies that have surrounded this iconic structure. Stay tuned for a deeper understanding of the intricate tapestry that weaves together religion, history, and architecture in the story of Babri Masjid

Unraveling Inscriptions: Decoding Babri Masjid’s Enigmatic Past

Survey and Surprises: The British East India Company’s surveyor, Francis Buchanan-Hamilton, conducted a survey of the Gorakhpur Division in 1813–14, leaving behind a report that hinted at intriguing aspects of the Babri Masjid’s history. Kishore Kunal, examining the original report, revealed that the Hindus attributed destruction to Aurangzeb, yet an inscription on the mosque’s walls pointed to its construction by Babur. However, doubts lingered about the authenticity of these inscriptions, adding complexity to the mosque’s narrative.

Conflicting Claims: In 1838, British surveyor Montgomery Martin asserted that the pillars in the mosque were sourced from a Hindu temple, a claim disputed by some historians, including R. S. Sharma. The debate over temple demolition allegations emerged only in the 18th century, according to these scholars, challenging the narrative surrounding the mosque’s construction materials.

Legal Petitions and Allah’s Inscription: In 1877, Syed Mohammad Asghar, the Mutawalli of the mosque, filed a petition stating that Babur inscribed “Allah” above the door. The district judge confirmed this, but no other inscriptions were recorded. This Allah-centric claim added a religious layer to the site’s contested history.

Archaeological Finds and Controversies: In 1889, archaeologist Anton Führer discovered three inscriptions, including Quranic verses and Persian poetry, attributing the mosque’s construction to figures associated with Babur. Despite contradictions in dates, Führer published the information in 1891. Writer Kishore Kunal, however, dismissed all inscriptions as fake, suggesting they were added much later, around 285 years after the mosque’s supposed construction in 1528.

Temporal Puzzle and Historical Disputes: Kunal proposed an alternative theory, suggesting the mosque was built around 1660 by Governor Fedai Khan of Aurangzeb, who allegedly demolished several temples in Ayodhya. Lal Das’s account in Awadh-Vilasa from 1672 accurately describes the janmasthan but makes no mention of a temple at the site. These contentions and reinterpretations cast a shadow over the historical authenticity of the Babri Masjid.

Controversial Manuscripts and Missing Links: In the mid-19th century, Muslim activist Mirza Jan quoted from the alleged manuscript “Sahifa-I-Chihil Nasaih Bahadur Shahi,” linking mosques’ construction after demolishing Hindu temples. The manuscript’s existence remains elusive, raising doubts about the reliability of Mirza Jan’s claims. Scholar Stephan Conermann further questioned the credibility of Mirza Jan’s book, adding another layer of uncertainty to the historical puzzle of Babri Masjid.

As we delve deeper into the intricate layers of Babri Masjid’s history, the conflicting inscriptions and contested narratives continue to unravel, leaving us with more questions than answers. Stay tuned for the next chapter in this journey through time and controversy

Unraveling the Fable of Musa Ashiqan: Myth or Reality?

Historical Accounts and the Sufi Saints: According to Maulvi Abdul Ghaffar’s early 20th-century text and corroborating historical sources investigated by historian Harsh Narain, a captivating tale unfolds. It recounts a young Babur’s journey from Kabul to Awadh (Ayodhya) in disguise, masquerading as a Qalandar, a Sufi ascetic, perhaps on a fact-finding mission. During his time in Awadh, Babur reportedly encountered two Sufi saints, Shah Jalal and Sayyid Musa Ashiqan, setting the stage for a mystical encounter.

The Pledge for Blessings and Conquest: In exchange for the blessings necessary for conquering Hindustan, Babur is said to have made a significant pledge to the Sufi saints. Unfortunately, the specifics of this pledge are not clearly outlined in the 1981 edition of Ghaffar’s book. The enigmatic nature of the pledge adds an air of mystery to the narrative, leaving room for interpretation and speculation.

Missing Details in Later Editions: The 1981 edition of Ghaffar’s book, which stands as a key source for this fable, lacks explicit details about the pledge made by Babur in return for the blessings from the Sufi saints. The absence of these details raises questions about the completeness and accuracy of the historical account, contributing to the complexity of the Babri Masjid’s narrative.

Historical Controversies and Interpretations: Lala Sita Ram, who had access to an older edition of Ghaffar’s book in 1932, offered additional insights. According to Ram, the Sufi saints purportedly pledged their blessings to Babur on the condition that he promised to build a mosque after demolishing the Janmasthan temple. Babur, it is claimed, accepted this condition, marking a pivotal moment in the historical trajectory of the disputed site.

Mythical Layers and Interpretive Challenges: The fable of Musa Ashiqan adds mythical layers to the historical account of Babur’s connection to Ayodhya. The interpretive challenges stemming from varying editions of historical texts and the absence of explicit details surrounding the pledge continue to fuel debates and controversies surrounding the true nature of events leading to the construction of the Babri Masjid. As we delve further into the complex layers of Babri Masjid’s history, the interplay between myth and reality becomes increasingly intricate. Stay tuned for the next installment in our exploration of this enigmatic historical saga

Alternative Theories: Unraveling Diverse Perspectives on Babri Masjid’s Origins

Delhi Sultanate Influence: Contrary to the predominant narrative associating the Babri Masjid with Babur’s era, some historians propose a different timeline. Arguing that the mosque may have been constructed during the Delhi Sultanate period (13th–15th century), R. Nath emphasizes architectural nuances that, according to him, align more with the pre-Mughal architectural style. This perspective challenges the widely accepted notion of the mosque’s origin.

Pre-Mughal Architectural Clues: R. Nath’s stance is rooted in an analysis of the mosque’s architectural features, suggesting a style that predates the Mughal era. This alternative viewpoint adds a layer of complexity to the Babri Masjid’s history, prompting a reconsideration of the prevalent belief in its construction during Babur’s reign.

Diverse Claims Beyond Hinduism: The contested site of Babri Masjid is not merely a focal point for Hindu-Muslim disputes. Jains and Buddhists also stake their claims, contributing further layers to the historical debate. According to Jain Samata Vahini, the mosque stands on the ruins of a 6th-century Jain temple, introducing a Jain perspective to the contentious narrative. Simultaneously, Udit Raj’s Buddha Education Foundation contends that the Babri Masjid was constructed atop a Buddhist shrine, highlighting the multiplicity of historical narratives that converge at this site.

Jain and Buddhist Assertions: Jains argue that the mosque’s existence veils the remnants of a significant Jain temple dating back to the 6th century. This assertion not only challenges the dominant narratives of the site but also underscores the diverse religious heritage that has left its imprint on Ayodhya over the centuries. Similarly, Buddhists, through the Buddha Education Foundation, present the intriguing possibility that the Babri Masjid may have been established over a Buddhist shrine. These diverse claims underline the complex historical tapestry that surrounds the Babri Masjid, revealing a multifaceted history that extends beyond Hindu-Muslim dynamics.

As we navigate through the various historical perspectives and alternative theories surrounding the Babri Masjid, it becomes evident that the site is not only a symbol of religious contention but also a repository of diverse historical narratives waiting to be explored and understood. The next installment will delve deeper into these complexities, shedding light on the intricate interplay of history, religion, and divergent claims at the heart of Ayodhya

Temple Construction Attempts in the 1880s: A Historical Prelude to Babri Masjid’s Controversy

1853: Hanuman Garhi Occupation and Rising Tensions: The 1880s temple construction attempts at the Babri Masjid find their roots in the events of 1853 when armed Hindu ascetics from the Hanuman Garhi temple occupied the mosque. This occupation led to periodic violence in the following years, prompting the civil administration to intervene. However, permission for temple construction or worship at the site was denied, setting the stage for future conflicts.

1855: Gulam Hussain and the Boundary Wall: In 1855, Gulam Hussain and a group of Sunni Muslims contested the Hindu occupation, asserting that the mosque site was originally a Hanuman temple. Following a Hindu-Muslim clash, a boundary wall was constructed to prevent further disputes. This wall divided the mosque premises into two courtyards, with Muslims praying in the inner courtyard. The Mahant of the Hanuman Garhi temple responded by erecting a raised platform in 1857, marking the supposed site of Rama’s birth. Hindus conducted prayers on a “Ram Chabutara” in the outer courtyard.

1883: Hindu Temple Construction Effort: In 1883, Hindus initiated an effort to construct a temple on the raised platform. Muslim protests ensued, leading the deputy commissioner to prohibit temple construction on January 19, 1885. In response, Hindu Mahant Raghubar Das filed a civil suit before the Faizabad Sub-Judge on January 27, 1885. The Muslim trustee argued that the entire land belonged to the mosque.

Legal Battles and Status Quo (1885-1886): The legal battle unfolded as the Sub-Judge Pandit Hari Kishan Singh dismissed the suit on December 24, 1885. The District Judge F.E.A. Chamier upheld this decision on March 18, 1886, ordering the maintenance of status quo despite acknowledging the sacred nature of the land for Hindus. A subsequent appeal before Judicial Commissioner W. Young was also dismissed on November 1, 1886. These legal decisions set the precedent for the contested nature of the site.

1934: Hindu-Muslim Riot and Reconstruction: On March 27, 1934, Ayodhya witnessed a Hindu-Muslim riot triggered by cow slaughter in the nearby Shahjahanpur village. The Babri Masjid suffered damages during the riots, with walls and one of the domes affected. These were reconstructed by the British Indian government, marking another episode in the tumultuous history surrounding the contentious site.

The 1880s temple construction attempts serve as a crucial chapter in the complex narrative of the Babri Masjid, foreshadowing the protracted legal battles and communal tensions that would later come to define its history. Stay tuned for the next segment, where we unravel more layers of this historical tapestry

Shia–Sunni Dispute Over Babri Masjid: Legal Wrangling and Historical Claims

In 1936, the United Provinces government introduced the U.P. Muslim Waqf Act, aimed at the improved administration of waqf properties within the state. Subsequently, the Babri Masjid and its adjacent graveyard, known as Ganj-e-Saheedan Qabristan, were registered as Waqf no. 26 Faizabad with the UP Sunni Central Board of Waqfs. However, this move sparked a Shia–Sunni dispute over ownership.

The Shia faction contested the Sunni claim to the mosque, asserting that Mir Baqi, the mosque’s builder, was a Shia. To address the contention, the Commissioner of Waqfs initiated an inquiry. The inquiry’s findings, published in an official gazette on February 26, 1944, concluded that the mosque rightfully belonged to the Sunnis. The rationale behind this decision rested on the belief that Babur, who commissioned the mosque, was a Sunni.

In response to this determination, the Shia Central Board took the matter to court in 1945, challenging the Sunni ownership of the Babri Masjid. The legal battle unfolded, culminating in a significant ruling on March 23, 1946. Judge S. A. Ahsan delivered a verdict in favor of the UP Sunni Central Board of Waqfs, reinforcing the Sunni claim to the Babri Masjid based on historical and religious grounds.

The Shia–Sunni dispute over the Babri Masjid, entrenched in legal intricacies and historical interpretations, added another layer of complexity to the ongoing narrative of the contested site. This legal chapter in the mosque’s history foreshadowed the prolonged legal battles and communal tensions that would intensify in the subsequent decades. Stay tuned for more insights into the multifaceted history of the Babri Masjid

Babri Masjid Controversy: Unraveling the Placement of Hindu Idols

Recitation and Controversial Night (December 22–23, 1949): In December 1949, the Babri Masjid, located in Ayodhya, witnessed a pivotal moment that would shape its contentious history. The Akhil Bharatiya Ramayana Mahasabha, a Hindu organization, orchestrated a non-stop nine-day recitation of the Ramacharitamanas just outside the mosque. As this event concluded on the night of December 22–23, a group of 50–60 individuals entered the mosque premises and placed idols of Lord Rama.

Locking the Gates and Government Intervention: Following the placement of Hindu idols, the organizers invited Hindu devotees to visit the mosque for darshan. As thousands flocked to the site, the government declared the mosque a disputed area and promptly locked its gates on the morning of December 23. Home Minister Vallabhbhai Patel and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru took swift action, instructing Chief Minister Govind Ballabh Pant and Uttar Pradesh Home Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri to have the idols removed.

Legal Challenges and Lawsuits (1950–1961): In response to the government’s directive, on January 16, 1950, Gopal Singh Visharad filed a civil suit in the Faizabad Court, seeking permission for Hindus to worship Rama and Sita at the disputed site. This marked the initiation of legal battles that would echo through the decades. In 1959, the Nirmohi Akhara, a Hindu religious institution, filed another lawsuit demanding possession of the mosque. On December 18, 1961, the Uttar Pradesh Sunni Central Waqf Board entered the legal arena, filing a lawsuit seeking possession of the site and the removal of idols from the mosque premises.

The placement of Hindu idols in 1949 proved to be a watershed moment, setting in motion a series of legal disputes that would define the Babri Masjid controversy for years to come. The subsequent lawsuits introduced multiple perspectives and claimants, underscoring the complex interplay of history, religion, and legal intricacies surrounding this disputed site. Stay tuned for further exploration of the Babri Masjid’s intricate tapestry in the upcoming segments of this series

Babri Masjid Demolition: Unraveling the Tragic Chapter in History

VHP’s Campaign and Rath Yatras (1984–1986): In April 1984, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) launched a campaign advocating Hindu access to the Babri Masjid and other structures believed to be constructed over Hindu shrines. This initiative aimed to garner public support, and to achieve this, the VHP organized nationwide rath yatras (chariot processions). The first such procession, from Sitamarhi to Ayodhya, unfolded in September–October 1984. Although the campaign briefly halted following the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, it resumed in 25 locations on October 23, 1985. On January 25, 1986, local lawyer Umesh Chandra Pandey appealed to a court to lift restrictions on Hindu worship at the Babri Masjid.

Rajiv Gandhi’s Government and Unlocking of Gates (1986): Responding to Pandey’s appeal, the Rajiv Gandhi government ordered the removal of locks on the Babri Masjid gates. Prior to this, the only Hindu ceremony permitted was an annual puja conducted by a Hindu priest. Post the government’s decision, all Hindus were granted access to the site, effectively transforming the mosque into a site of dual worship, serving both Hindu and Muslim communities.

Escalating Communal Tensions (1989–1992): Communal tension heightened when the VHP obtained permission for a shilanyas (stone-laying ceremony) at the disputed site just before the national election in November 1989. L. K. Advani, a senior Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader, initiated a rath yatra covering 10,000 km and heading towards Ayodhya. On December 6, 1992, leaders from the BJP, VHP, and Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) congregated at the site for prayers and symbolic kar seva (religious service). At noon, a teenage kar sevak was propelled onto the dome, signaling the breach of the outer cordon. Subsequently, a large number of kar sevaks demolished the Babri Masjid in a tragic turn of events.

The demolition of the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992, marked a dark chapter in India’s history, fueling communal tensions and leaving an indelible impact on the nation’s socio-political landscape. The echoes of this event continue to reverberate, shaping the complex narrative surrounding the Babri Masjid controversy. Stay tuned for more insights into the aftermath and the protracted legal battles that ensued

Aftermath of the Babri Masjid Demolition: Unraveling the Ripples

Communal Riots and Loss of Lives: The demolition of the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992, triggered immediate and widespread communal riots between Hindus and Muslims across India. The aftermath of the demolition was marred by violence, resulting in an estimated 2,000 fatalities. Six weeks of intense riots erupted in Bombay (now Mumbai), claiming the lives of approximately 900 people. The nation found itself grappling with the consequences of a deeply divisive event that left scars on its social fabric.

Escalation of Jihadist Violence: The demolition had broader repercussions, influencing jihadist outfits like the Indian Mujahideen and Lashkar-e-Taiba. These groups cited the Babri Masjid’s demolition as justification for launching attacks against India. The scars of this event continued to resonate through acts of violence, showcasing the profound impact of the Babri Masjid’s destruction on the geopolitical landscape.

Dawood Ibrahim and the 1993 Bombay Bombings: Dawood Ibrahim, a notorious crime boss associated with D-Company, was reportedly infuriated by the demolition of the Babri Masjid. He is wanted in India for his alleged involvement in the 1993 Bombay bombings, which claimed 257 lives. The connections between the Babri Masjid’s demolition and subsequent acts of terrorism underscored the far-reaching consequences of the event.

Transformation of the Site: In the aftermath, the site of the Babri Masjid underwent a transformation, evolving into a pilgrimage destination. Pilgrims from various parts of the country visited the site, reflecting its newfound significance in the collective consciousness.

Souvenirs and Lingering Tensions: The site, with its souvenir stalls, became a microcosm of the lingering tensions. Videos depicting the demolition played on a loop at souvenir stalls, reflecting the divisive nature of the event. The scars of Babri Masjid’s demolition, etched into the national memory, were palpable even in the commerce around the site.

The aftermath of the Babri Masjid demolition was characterized by communal strife, geopolitical repercussions, and a shift in the site’s symbolism from a mosque to a contentious pilgrimage destination. The echoes of this pivotal moment continue to shape narratives and debates in contemporary India. Stay tuned for further exploration into the legal battles and the eventual resolution of the Babri Masjid controversy

Regional Impact of Babri Masjid’s Demolition: Ripple Effects Beyond Borders

Bangladesh: The aftershocks of the Babri Masjid’s demolition reverberated beyond India, reaching Bangladesh. Riots erupted in Bangladesh in the aftermath, resulting in the destruction of hundreds of shops, homes, and temples belonging to Hindus. The violence created a ripple effect, leading to heightened tensions and communal strife in the region.

Pakistan: In neighbouring Pakistan, widespread retaliatory attacks unfolded against Hindu and Jain temples. Shockingly, the police did not intervene, exacerbating the communal tensions. The aftermath of the demolition saw a surge in reprisal attacks against Hindus, further fueling the already volatile situation. The violence against minorities in Pakistan became a focal point for right-wing Hindu nationalists.

Impact on India-Pakistan Relations: The Babri Masjid’s demolition and the ensuing violent repercussions had a lasting and detrimental impact on relations between India and Pakistan. The negative fallout strained diplomatic ties, contributing to ongoing tensions between the two nations. The episode became a point of contention in the complex history of the Indian subcontinent, influencing the geopolitical landscape for years to come.

International Appeals: The consequences of the demolition reached international forums. In 1995, the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) appealed to the United Nations, urging protection for Hindus in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Kashmir. The appeal underscored the transnational repercussions of the event and its implications for minority communities beyond India’s borders.

The regional impact of the Babri Masjid’s demolition extended far beyond India, leaving scars on the communal fabric in Bangladesh and Pakistan. Additionally, it played a role in shaping the dynamics between India and Pakistan, contributing to the complex geopolitical narrative in the region. The repercussions of this pivotal event continue to echo through the collective memory of South Asia. Stay tuned for a deeper exploration into the legal aftermath and the eventual resolution of the Babri Masjid controversy

Liberhan Commission: Unveiling Responsibility for Babri Masjid’s Demolition

Commission’s Establishment and Mandate: In the wake of the Babri Masjid’s demolition, the Indian government established the Liberhan Commission to investigate the circumstances leading to the destruction of the mosque. The commission’s mandate was to scrutinize the events surrounding the demolition and identify individuals responsible for orchestrating or contributing to the act.

Blame on Senior Leaders: The findings of the Liberhan Commission were both comprehensive and damning. The report held 68 individuals accountable for the demolition, implicating senior leaders from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), and Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP). Prominent figures such as Atal Bihari Vajpayee, LK Advani, and Chief Minister Kalyan Singh faced criticism for their roles in the demolition.

Pre-Planned Conspiracy: The commission’s revelations went beyond immediate culpability, suggesting a pre-planned conspiracy. According to a 2005 book by Maloy Krishna Dhar, a former Joint Director of the Intelligence Bureau (IB), senior leaders of the RSS, BJP, VHP, and Bajrang Dal had allegedly orchestrated the demolition nearly 10 months in advance. This assertion implied a deliberate and calculated effort to bring down the Babri Masjid.

Political Allegations: Maloy Krishna Dhar’s book also ventured into the realm of political dynamics, suggesting that leaders of the Indian National Congress, including Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao and Home Minister S B Chavan, were aware of warnings about the impending demolition but chose to ignore them for perceived political gains. The intertwining of political motivations with the events surrounding the Babri Masjid added another layer of complexity to the already charged narrative.

The Liberhan Commission’s findings not only assigned responsibility to key figures in the demolition but also shed light on the intricate planning that allegedly preceded the act. The political ramifications outlined in the report highlighted the multifaceted nature of the Babri Masjid controversy, intertwining religion, politics, and power dynamics. Stay tuned for further exploration into the legal repercussions and the eventual resolution of this contentious chapter in Indian history

Archaeological Excavations at Ayodhya: Unearthing Layers of History

Court-Ordered Exploration: In response to the contentious dispute over the Babri Masjid site, an Indian court in 2003 mandated the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) to conduct a comprehensive excavation to unveil the historical layers beneath the rubble. The excavation, carried out from March 12, 2003, to August 7, 2003, aimed to shed light on the nature of the structures that existed before the Babri Masjid.

Discoveries and ASI Report: The excavation yielded a substantial 1360 discoveries, offering a glimpse into the rich historical tapestry beneath the disputed site. The ASI compiled its findings and submitted a detailed report to the Allahabad High Court. The summary of the report suggested the presence of a 10th-century shrine beneath the mosque, adding layers of complexity to the historical narrative.

Chronological Unraveling: The ASI team’s analysis indicated human activity at the site dating back to the 13th century BC. Successive layers unveiled the Shunga period (2nd-1st century BC) and the Kushan period. Notably, during the early medieval period (11–12th century), a structure of approximately 50 meters with a north–south orientation was constructed. Over time, this structure underwent multiple phases and floor additions. The ASI’s conclusion posited that the disputed structure of the Babri Masjid was built upon this pre-existing construction during the early 16th century.

Controversial Interpretations: While the ASI findings were accepted by the Allahabad High Court, they faced immediate dispute from Muslim groups. The Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust (Sahmat) criticized the report, contending that features such as the “presence of animal bones” and the use of ‘surkhi’ and lime mortar were indicative of Muslim presence, negating the possibility of a Hindu temple underneath. Debates also arose regarding the alleged ‘pillar bases,’ with some archaeologists contesting their existence.

Legal Validation: Despite the controversies, the Allahabad High Court upheld the ASI’s findings. The excavation not only unearthed physical remnants but also added layers of complexity to the Babri Masjid controversy, intertwining archaeological evidence with the historical and legal dimensions. Stay tuned for further exploration into the legal aftermath and the eventual resolution of this enduring dispute

Title Cases Verdict: Unraveling the Legal Tapestry

High Court Pronouncement: In a significant legal chapter, the Allahabad High Court delivered its verdict on the Ayodhya land title case on September 30, 2010. The intricate legal battle, deeply entwined with religious sentiments, sought resolution through a comprehensive judgment. The three-judge panel ruled that the 1.1 hectares (2+3⁄4 acres) of the Ayodhya land be partitioned into three segments. One-third was earmarked for the construction of the Ram temple, representing Ram Lalla or Infant Lord Rama and managed by the Hindu Maha Sabha. Another one-third was allocated to the Islamic Uttar Pradesh Sunni Central Waqf Board, and the remaining portion went to Nirmohi Akhara, a Hindu religious denomination. While unanimity was lacking on whether the disputed structure replaced a pre-existing temple, the court did acknowledge the presence of a Hindu religious building predating the mosque, with archaeological findings being crucial evidence.

Archaeological Support: The verdict heavily leaned on the archaeological evidence presented by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). The ASI’s excavations were instrumental in establishing the existence of a substantial Hindu religious structure before the construction of the Babri Masjid. This evidence played a pivotal role in shaping the court’s determination regarding the historical layers beneath the disputed site.

Supreme Court Deliberation: The legal saga continued with the Supreme Court taking up the title dispute cases in a five-judge bench from August to October 2019. The Court, examining the ASI findings, noted that the Babri Masjid was built upon a “structure” with distinctly indigenous and non-Islamic architecture. On November 9, 2019, the Supreme Court issued a historic judgment, directing the land to be handed over to a trust for the construction of the Hindu temple. Simultaneously, the government was instructed to allocate an alternative 2-hectare (5-acre) plot to the Uttar Pradesh Sunni Central Waqf Board for the construction of a mosque. This marked a crucial milestone in the legal resolution of the longstanding Ayodhya land dispute, intertwining historical, archaeological, and religious dimensions

Explanatory Notes: Unraveling Historical Accounts

Ownership under Jai Singh II (1717): Professor R. Nath delves into historical records and concludes that Jai Singh II acquired the land of Rama Janmasthan in 1717. The intriguing aspect is that the ownership was vested in the deity itself. The Mughal State recognized and enforced the hereditary title of ownership from 1717. A letter dated 1723 from gumastha Trilokchand notes that the establishment of Jaisinghpura removed impediments that had previously restricted people from taking ritual baths in the Saryu river during Muslim administration.

Aurangzeb’s Role in Demolition: Historical accounts, including Johann Bernoulli’s translation of Joseph Tiefenthaler’s Descriptio Indiae (c. 1772), shed light on the events around Emperor Aurangzeb’s actions. The fortress called Ramcot was demolished by Aurangzeb, who is said to have ordered the construction of a Muslim temple with triple domes at the same location. Controversy surrounds whether it was constructed by Aurangzeb or ‘Babor’ (Babur). Tiefenthaler’s account mentions black stone pillars from the fortress supporting the interior arcades of the mosque.

Construction under Meer Baqi and Tughra Inscriptions: The inscription on the Babri Masjid attributes its construction to Meer Baqi, a nobleman, by order of King Babur. The anagram “good works are lasting” is interpreted to represent the year 935. The Tughra (calligraphic monogram) accompanying the inscription emphasizes the oneness of God and the prophethood of Mohammad. The inscriptions also trace the genealogy of rulers back to Babur, emphasizing the mosque’s historical significance.

Testimony and Proclamation in Tughra: The inscriptions on the Babri Masjid include a detailed testimony and proclamation related to its construction. The victorious lord Mooheyoo Din Aulumgir, commonly known as Aurangzeb, is mentioned as the destroyer of infidels. The Tughra emphasizes the oneness of God, Mohammad as his servant and prophet, and declares the construction as a noble erection.

These explanatory notes provide glimpses into the historical narratives, conflicting perspectives, and intricate details surrounding the Babri Masjid’s construction, demolition, and the subsequent legal battles

References: Unraveling the Layers of Ayodhya

- BBC: A reliable source for contemporary updates and analysis on the Ayodhya issue.[^1^]

- Timeline: Ayodhya holy site crisis (BBC News): An archived timeline providing a comprehensive overview of events related to the Ayodhya dispute.[^2^]

- Hiltebeitel, Alf. (2009). Rethinking India’s Oral and Classical Epics: A scholarly work that explores Draupadi’s significance among different communities, shedding light on diverse perspectives.[^3^]

- Udayakumar, S.P. (1997). Historicizing Myth and Mythologizing History: An insightful article from Social Scientist that discusses the ‘Ram Temple’ drama and its historical context.[^4^]

- PTI – Economic Times: Information about the Archaeological Survey of India’s excavation report and its publication as a book.[^5^]

- Times Now: Details on seven pieces of evidence unearthed by the Archaeological Survey of India supporting the existence of a temple at Ayodhya.[^6^]

- India Today – ASI findings in Ayodhya verdict: A brief on the findings of the Archaeological Survey of India, cited in the Ayodhya verdict by the Supreme Court.[^7^]

- van der Veer, Peter (1992): A scholarly article discussing Ayodhya and Somnath, providing historical context and contested narratives.[^8^]

- Outlook – Tracing The History of Babri Masjid: An insightful piece discussing the historical context of the Babri Masjid, its construction, and the subsequent disputes.[^9^]

- Guha, Ramachandra (2007). India After Gandhi: A comprehensive book covering the history of India after gaining independence, including the Ayodhya issue.[^10^]

- Khalid, Haroon (2019). The Wire: An article discussing the impact of the Babri Masjid demolition on inter-religious ties in Pakistan.[^11^]

- The Morning Chronicle (2018): Information on the reactions in Pakistan and Bangladesh following the Babri Masjid demolition.[^12^]

- BBC News – Ayodhya dispute: The complex legal history: A comprehensive article providing insights into the legal history of the Ayodhya dispute.[^13^]

- The Times of India – Ram Mandir verdict: Information on the 2019 Supreme Court verdict on the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid case.[^17^]

- India Today – Dhannipur: Details about the site allotted to the Uttar Pradesh Sunni Central Waqf Board for the construction of a mosque.[^18^]

- Business Standard – Mood in Dhannipur: An article capturing the sentiments in Dhannipur, the village chosen for the mosque’s construction.[^19^]

- The Siasat Daily – Construction of Ayodhya mosque: Information on the commencement of the Ayodhya mosque’s construction on Republic Day.[^20^]

- NDTV.com – Ayodhya Mosque Work: Reports on the beginning of Ayodhya mosque work on Republic Day.[^21^]

- Flint, Colin (2005). The Geography of War and Peace: A book providing insights into the geography of conflicts, relevant to understanding the Ayodhya issue.[^22^]

- Multiple sources (Jaishankar, K. et al.): Various sources stating the fact that before the 1940s, the mosque was referred to as Masjid-i Janmasthan.[^23^]

- Narain, Harsh (1993). The Ayodhya Temple Mosque Dispute: A crucial work focusing on Muslim sources, offering insights into the Ayodhya dispute.[^24^]

- Elst, Koenraad (1995). “The Ayodhya Debate”: An article discussing various perspectives on the Ayodhya issue.[^25^]

- Jain, Rama and Ayodhya (2013): A book delving into the connection between Lord Rama and Ayodhya, exploring historical and cultural aspects.[^26^]

- Kunal, Kishore (2016). Ayodhya Revisited: A comprehensive exploration of Ayodhya’s history, including the Babri Masjid demolition.[^27^]

- Professor R. Nath (Explanatory Notes): Insights into the historical records, ownership, and events related to Ayodhya.[^28^]

- References and Citations: A list of references, citations, and further readings providing diverse perspectives on the Ayodhya issue.[^29^]

These references offer a multifaceted understanding of the Ayodhya dispute, spanning historical, legal, and cultural dimensions